Mass-scale sheltering of Hurricane Harvey evacuees:

Infectious disease surveillance and prevention

Wendy Chung, MD

Dallas County Health and Human Services, Chief Epidemiologist

A s Hurricane Harvey made landfall

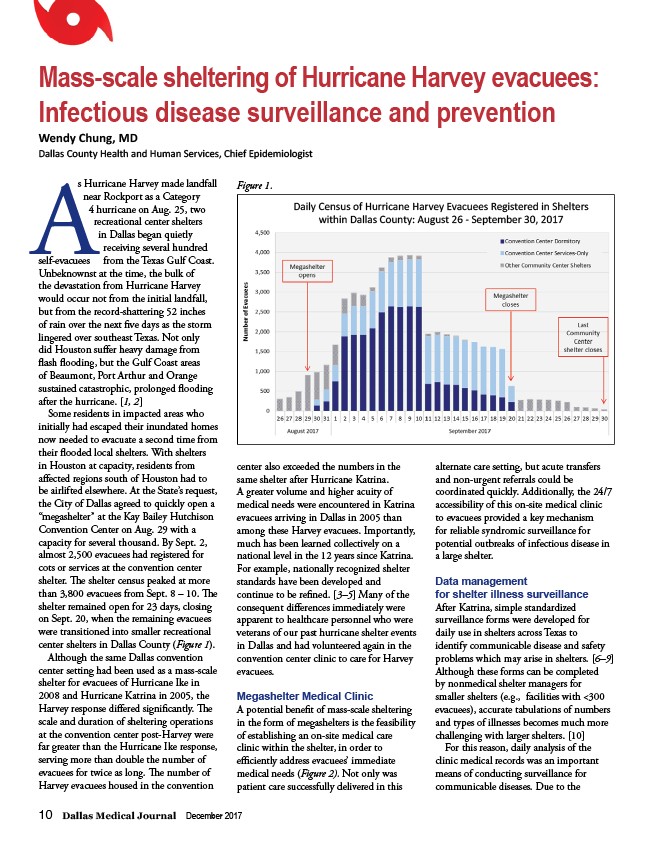

Figure 1. near Rockport as a Category

4 hurricane on Aug. 25, two

Daily Census of Hurricane Harvey Evacuees Registered in Shelters

recreational center shelters

in Dallas began quietly

receiving several hundred

self-evacuees from the Texas Gulf Coast.

Unbeknownst at the time, the bulk of

the devastation from Hurricane Harvey

would occur not from the initial landfall,

but from the record-shattering 52 inches

of rain over the next fi ve days as the storm

lingered over southeast Texas. Not only

did Houston suff er heavy damage from

fl ash fl ooding, but the Gulf Coast areas

of Beaumont, Port Arthur and Orange

sustained catastrophic, prolonged fl ooding

after the hurricane. 1, 2

Some residents in impacted areas who

initially had escaped their inundated homes

now needed to evacuate a second time from

their fl ooded local shelters. With shelters

in Houston at capacity, residents from

aff ected regions south of Houston had to

be airlifted elsewhere. At the State’s request,

the City of Dallas agreed to quickly open a

“megashelter” at the Kay Bailey Hutchison

Convention Center on Aug. 29 with a

capacity for several thousand. By Sept. 2,

almost 2,500 evacuees had registered for

cots or services at the convention center

shelter. Th e shelter census peaked at more

than 3,800 evacuees from Sept. 8 – 10. Th e

shelter remained open for 23 days, closing

on Sept. 20, when the remaining evacuees

were transitioned into smaller recreational

center shelters in Dallas County (Figure 1).

Although the same Dallas convention

center setting had been used as a mass-scale

shelter for evacuees of Hurricane Ike in

2008 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the

Harvey response diff ered signifi cantly. Th e

scale and duration of sheltering operations

at the convention center post-Harvey were

far greater than the Hurricane Ike response,

serving more than double the number of

evacuees for twice as long. Th e number of

Harvey evacuees housed in the convention

within Dallas County: August 26 - September 30, 2017

center also exceeded the numbers in the

same shelter after Hurricane Katrina.

A greater volume and higher acuity of

medical needs were encountered in Katrina

evacuees arriving in Dallas in 2005 than

among these Harvey evacuees. Importantly,

much has been learned collectively on a

national level in the 12 years since Katrina.

For example, nationally recognized shelter

standards have been developed and

continue to be refi ned. 3–5 Many of the

consequent diff erences immediately were

apparent to healthcare personnel who were

veterans of our past hurricane shelter events

in Dallas and had volunteered again in the

convention center clinic to care for Harvey

evacuees.

Megashelter Medical Clinic

A potential benefi t of mass-scale sheltering

in the form of megashelters is the feasibility

of establishing an on-site medical care

clinic within the shelter, in order to

effi ciently address evacuees’ immediate

medical needs (Figure 2). Not only was

patient care successfully delivered in this

10 Dallas Medical Journal December 2017

alternate care setting, but acute transfers

and non-urgent referrals could be

coordinated quickly. Additionally, the 24/7

accessibility of this on-site medical clinic

to evacuees provided a key mechanism

for reliable syndromic surveillance for

potential outbreaks of infectious disease in

a large shelter.

Data management

for shelter illness surveillance

After Katrina, simple standardized

surveillance forms were developed for

daily use in shelters across Texas to

identify communicable disease and safety

problems which may arise in shelters. 6–9

Although these forms can be completed

by nonmedical shelter managers for

smaller shelters (e.g., facilities with <300

evacuees), accurate tabulations of numbers

and types of illnesses becomes much more

challenging with larger shelters. 10

For this reason, daily analysis of the

clinic medical records was an important

means of conducting surveillance for

communicable diseases. Due to the